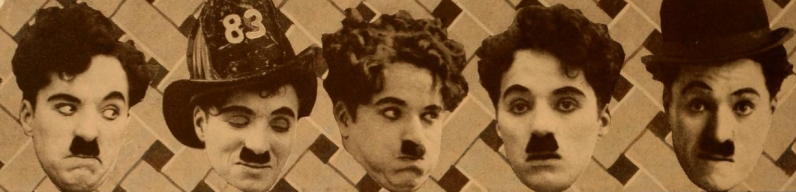

Few figures in motion-picture history have cast as long and luminous a shadow as Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin. His bowler hat, cane, and endearing waddle made him one of the most recognizable faces on Earth. Yet behind that comic mustache was a man whose genius, controversy, and resilience defined the art of cinema itself.

By Allan R. Ellenberger

Charlie Chaplin was born on April 16, 1889, in the slums of London to vaudeville performers Charles and Hannah Chaplin. Poverty, an absent father, and a mother’s mental illness shaped his early years, forcing the young boy to fend for himself on the streets. But hardship also sharpened his gift for observation — that uncanny ability to find humor and humanity in suffering.

He joined a troupe of child entertainers, and by his teens he was a seasoned stage comedian. In 1910, Chaplin toured America with Fred Karno’s vaudeville company, where audiences were mesmerized by his elastic movements and expressive face. Hollywood soon took notice.

When he signed with Keystone Studios in 1913, Chaplin was an unknown — by 1915, he was a phenomenon. That’s when he introduced “The Little Tramp”, a lovable vagabond with a shabby suit and indomitable dignity. In short order, Chaplin became the first truly international movie star, his name is synonymous with silent film itself.

The Tramp Conquers the World

At Essanay, Mutual, and later First National, Chaplin perfected the art of the short comedy — The Tramp (1915), Easy Street (1917), and The Immigrant (1917) combined slapstick with social satire. In 1919, he co-founded United Artists with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith, ensuring creative independence that few filmmakers enjoyed.

Chaplin’s features — The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), City Lights (1931), and Modern Times (1936) — blended pathos and laughter in ways never seen before. When sound came to the screen, he resisted, insisting that his Tramp spoke a universal language. But in 1940, he finally embraced dialogue with The Great Dictator, a daring satire that mocked Adolf Hitler and fascism.

Exile and Reinvention

Chaplin’s politics, personal scandals, and relationships made him a lightning rod in postwar America. Accused of communist sympathies and moral impropriety, he was effectively exiled in 1952 after a trip abroad — his re-entry permit revoked by U.S. authorities. He settled in Switzerland with his fourth wife, Oona O’Neill, and their growing family.

Yet even from afar, Chaplin continued to create: A King in New York (1957) and A Countess from Hong Kong (1967) reflected his sharp wit and social conscience. In 1972, Hollywood finally made amends, presenting him with an Honorary Academy Award. The ovation lasted twelve minutes — the longest in Oscar history.

Chaplin with his wife Oona and six of their eight children (Jane and Christopher are absent) in 1961

The Final Act — and a Macabre Twist

Chaplin passed away peacefully on Christmas Day, 1977, at his lakeside estate in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland, at the age of 88. But even in death, his story took a bizarre turn. In March 1978, two mechanics, Roman Wardas and Gantscho Ganev, stole Chaplin’s coffin from its grave, demanding a ransom from his widow, Oona. The crime made headlines around the world — part tragedy, part dark comedy worthy of Chaplin himself.

After an extensive investigation, Swiss police captured the culprits and recovered Chaplin’s body eleven weeks later. His coffin was reburied beneath six feet of concrete to ensure that the Tramp would wander no more.

Legacy of Laughter

Charlie Chaplin’s artistry transcended words, time, and borders. His films still draw laughter and tears, reminding us that comedy can be both mirror and medicine. As Chaplin once said:

“To truly laugh, you must be able to take your pain and play with it.”

And play with it he did — turning the world’s sorrows into something sublime.

So, this month, as reels flicker in darkened rooms and a cane twirl in silhouette, we salute Charlie Chaplin, the eternal showman who made humanity his punchline — and his poetry.

Your perspective matters — leave a comment below and help keep Hollywood’s history a living dialogue.

Add comment

Comments