Ida Estelle Taylor was born in Wilmington, Delaware, on May 20, 1894. Her father and mother divorced early in her childhood, and she was raised mostly by her maternal grandparents. Little else of her childhood seems to have survived the heat of studio klieg lights and the glare of Old Hollywood desert sun. What did endure was the propriety and strict discipline that she learned as a youth from the guardians who instilled in her middle-class values. Taylor became a professional pianist and was well schooled in the codes of respectability. But from childhood she had an intensity of expression and physical magnetism which found their finest outlet in silent film.

By Allan R. Ellenberger

Taylor's career began in the theater and she made her Broadway debut in 1919 in Come-On, Charlie. Critics took note. Film came calling not long after and Hollywood saw in Taylor someone the camera loved: voluptuous, angular dark eyes and lashes, and a sultry confidence that looked sophisticated and new during the early 1920s. Taylor signed with the Fox Film Corporation after appearing in While New York Sleeps (1920), convincing audiences she was not one but two people as she seamlessly transitioned between ingénue and femme fatale. She was quickly typecast as the former but had proven that she was more than just eye candy; she could act within the melodramatic conventions of silent cinema.

Taylor continued to appear in important pictures throughout the 1920s. She worked back and forth between Paramount and MGM, appearing with John Gilbert in Monte Cristo (1922) and for Cecil B. DeMille in The Ten Commandments (1923).

She was a natural at historical roles that showcased her style and ability to command the screen. She played Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926) opposite Barrymore. The sultry Taylor was right at home playing a heavy-hitting femme fatale with allure dripping from every pore. Portraying characters as ambitious, exotic, and sensual as Lucrezia showcased Taylor's screen vamp persona better than most silent films fans can remember.

Unlike some actresses of her era, Taylor made the transition from silent films to talking pictures gracefully, her voice well suited to the medium. She starred in several important early talking pictures, including Cimarron (1931), one of Hollywood's most lavish productions up to that time. During the remainder of the 1930s, she slowly faded from the spotlight, eventually devoting herself to interests other than acting. One of these interests would become much more important to Taylor in later years than show business ever was.

Away from the camera, Taylor's personal life had long fascinated audiences. Her marriage to world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey on February 7, 1925 combined two of the decade's biggest stars: movie sex appeal and muscular athleticism. For several years they were one of the most photographed couples in America. Although plagued by celebrity pressures and extreme differences in temperament, Taylor and Dempsey remained married until 1931. After their divorce, Taylor was forever cemented in the public eye as both a vamp and starlet. She later married twice more (once to theatrical producer Paul Small), but neither of these unions surpassed Dempsey in terms of cultural impact. She bore no children. Increasingly over the years, Taylor focused her energies on helping others.

Taylor became an outspoken advocate for animals later in life. As president of the California Pet Owners Protective League and vice chairperson of the City Animal Regulation Commission, she became just as formidable as she had been glamorous.

Jack Dempsey and Estelle Taylor

She led a public battle against vivisection and mandatory rabies inoculation and advocated humane treatment of animals whom she felt could not defend themselves. Taylor was not simply making a name for herself with this organization either. She earned a reputation as someone who was not afraid to confront officials, would stand her ground and was never one to temper her beliefs for convenience or popularity. For many people in Los Angeles, Taylor became better known as that animal rights activists than movie star.

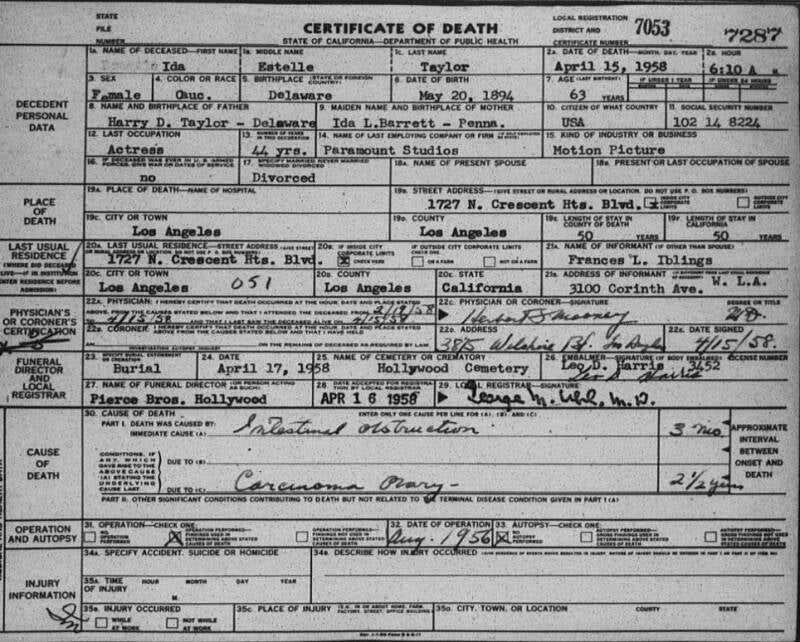

Estelle Taylor died from an intestinal obstruction due to ovarian cancer at her North Crescent Heights Boulevard home on April 15, 1958, at the age of sixty-three. Taylor's funeral took place two days later at the Pierce Brothers' Hollywood Chapel. Tributes at her funeral included wreaths formed as her favorite boxer and poodle placed at the foot of her casket – simple, heartfelt gestures that were perhaps more eloquent than words. She is interred at Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery (Garden of Beginnings, Sect. 2, Lot 9, Grave 402B), now called Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

In Hollywood Forever, Estelle Taylor remains both an emblem and a contradiction: a woman celebrated for beauty who refused to let beauty be her final story; a silent-screen siren whose most enduring voice emerged after the cameras stopped rolling. Her legacy lives not only in celluloid shadows and studio stills, but in the quieter, harder-won victories of compassion—proof that the power of a Hollywood name, when wielded with conviction, could echo far beyond the footlights.

Add comment

Comments