In December, the poinsettia comes to the doorsteps, the church aisles, the store windows and the dinner tables by some form of instinct. It is so familiar, its origins seem at once mythical and lost. But behind that explosion of red and green is a quiet immigrant tale of loss and resilience, Hollywood soil and a Swiss-born farmer named Albert Ecke, whose patient experimentation and stubborn faith turned an obscure Mexican weed into North America's Christmas flower.

By Allan R. Ellenberger

Albert Ecke, who popularized the poinsettia in America. Photo Credit: The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers/California State University San Marcos

The poinsettia had entered American life long before Ecke. Named for Joel Poinsett, the first United States minister to Mexico, who had introduced the plant to the U.S. in the early nineteenth century, the “flame flowers of the Holy Night” were admired for their color but remained delicate, short-lived, and difficult to grow. By the early twentieth century, the poinsettia had become associated with Christmas, but it was still, as Ecke put it, a novelty: a cut flower that wilted easily and stubbornly resisted commercial cultivation.

Albert Ecke was born on April 3, 1860, in Mahlwinkel, Germany, and trained as a schoolteacher, but his interests extended well beyond the classroom. Along with his wife, Henrietta, he operated a vegetarian sanitarium in Germany, a venture largely financed through Henrietta’s inheritance. The enterprise prospered, and the family—Albert, Henrietta, and their four children, Hans, Margaret, Paul, and Frieda—set their sights on expanding the business abroad. In 1902, they left Europe intending to establish a similar health retreat in Fiji.

Fate intervened mid-journey. After experiencing Southern California’s climate, they abandoned the Fiji plan entirely, recognizing that California offered something far better: land, sunlight, and possibility. The Eckes initially homesteaded in a place called Eagle Rock, which was then on the outskirts of the larger Los Angeles area. There they grew vegetables, fruit trees and flowers, such as iris and a few of the first poinsettias to naturalize in California.

In April 1904, tragedy struck the Ecke family in a devastating accident that changed their lives forever. While playing in the yard of their Eagle Rock home, eleven-year-old Margaret Ecke was fatally shot when her father, Albert, seated on the porch, picked up a rifle he did not realize was loaded. The weapon discharged, the bullet striking Margaret just above the heart. She was carried inside but died before medical help could arrive. Authorities ruled the shooting accidental, noting that Albert, newly arrived from Germany and barely able to speak English, was nearly incoherent with grief, insisting he had never intended to pull the trigger. The horrifying event was witnessed by other family members and neighbors, including Margaret’s siblings—Hans, Paul, and Frieda.

The loss shattered the family’s fragile sense of stability. Overcome by grief, the Eckes returned to Europe for a time, living briefly in Zurich before realizing they could not outrun the tragedy. By October of that year, they were back in California, carrying their sorrow with them as they attempted to rebuild their lives.

In 1906 the family relocated to Hayworth Avenue in Hollywood. Albert rented ten acres for a small price and farmed melons and tomatoes, setting aside a small portion of the lot for chrysanthemums and poinsettias. Albert also demonstrated a savvy real estate sense, selling a lot at a profit on Hayworth Avenue and buying a piece of property at 7204 Sunset Boulevard, on which he built a four family, seventeen-room flat in 1912. Farming and real estate land-buying were two sides of the same coin, each propping up the other as Albert looked for a cash crop that could support the family.

By 1909, Albert had started to experiment more purposefully with growing poinsettias in Eagle Rock. At the time there were only two varieties of poinsettias widely available – “True Red” and “Early Red”. Both were frail, short-lived and ill-suited for indoor use. Albert thought they could be better. Generations of cross-breeding and tireless trial and error led to hardier plants in hues of red, pink, white and yellow. His goal was simple: a poinsettia that could last. That could travel. That would live indoors.

Henrietta Ecke. Photo Credit: The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers/California State University San Marcos

A roadside sign stands before a sprawling poinsettia field near Sunset Hills Road and Doheny Drive, with the historic Doheny Courtyard Apartments visible in the far-left distance.

Success was far from immediate. Albert bought five acres of land in El Monte in 1915, dedicated solely to poinsettias. He mortgaged his future to buy the crop, but lost it. The following year a planting was wiped out by frost, and the family lost the land, plus another $500 in debt. The family dairy took in enough to survive. In 1917, after many failures, Albert had his breakthrough, selling his choicest blooms at Christmas, and showed that the plant was both beautiful and profitable.

The plant's connection to Christmas was well-known by that time and Albert could not have found a better time for his plants to come to the market. His son Paul, a young man at the time, created stands on Sunset Boulevard during the Christmas holidays that sold cut poinsettias from the field.

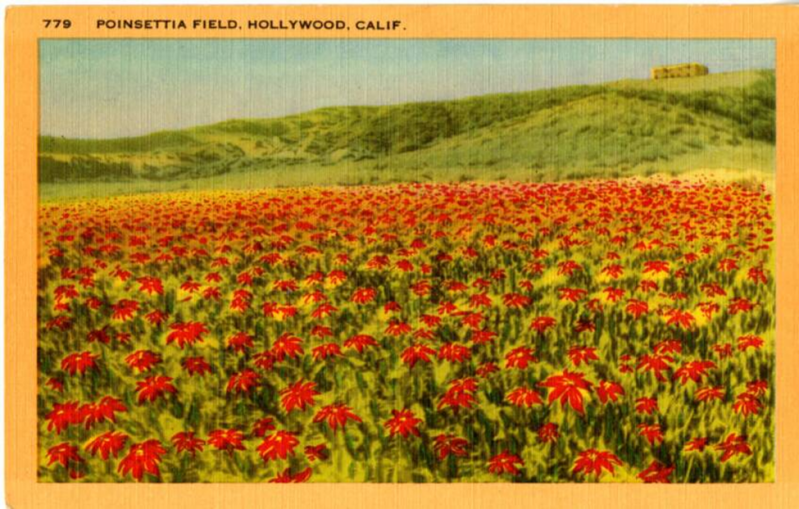

Miles of Sunset Boulevard burned with red in December. It was so dramatic, tourists would purchase postcards of the view. Hollywood became a billboard for the plant itself.

Developers took notice. In Westwood, the Janss Investment Company offered the Eckes rent-free land to beautify its growing community. Similar arrangements followed in Beverly Hills, where developers understood that color sold dreams as effectively as architecture. Empty Hollywood lots bloomed with poinsettias, transforming agriculture into civic decoration.

Postcard of a Poinsettia Field in Hollywood, (Photo Credit: Author’s Collection)

Postcard for "The Poinsettia: California's Christmas Flower." (Photo Credit: Author's Collection)

By 1918, the Eckes were sending cut flowers to New York, Chicago and St. Louis. But that same year, disaster struck again. Albert's son Hans died, the victim of Spanish flu. Albert himself would not live to see his vision in full bloom. He died on September 16, 1919, in San Bernardino. He was buried at Hollywood Cemetery, Section 10, Grave 546, not far from Hans. Henrietta would be buried at Chandler Gardens in 1945.

Control of the company went to Paul Ecke. He soon saw that the real estate rush in Hollywood would eventually squeeze out agriculture. He began moving the operation further south, eventually landing in Encinitas where long-term stability seemed possible, based on real estate and climate. There, Paul Ecke created what his father had only envisioned but not quite achieved: The first poinsettia cultivar that could be successfully grown as an indoor potted plant. He then distributed it across the country, forever changing the poinsettia from a seasonal cut flower into a living household tradition.

Looking North from Hacienda Park. The Eckes' poinsettia field in Hollywood Park. (Photo Credit: UCLA Library Special Collections)

The Ecke family would continue to influence the industry for many generations to come. Paul Ecke Jr. further expanded the business at an enormous rate after 1963, as did Paul Ecke III in 1992, who expanded cultivation into Guatemala. During this time, the family made contributions of land and facilities to schools, parks, and cultural institutions all over Southern California. The family sold the business to the Dutch Agribio Group in 2012, ending the long over 100-year history.

Son John Hans Ecke, died from the Spanish Flu. [Section 10, Grave 479)]

Albert Christoph Ecke [Section 10, Grave 546)]

Wife, Henriette Ecke (Chandler Gardens (Sect. 12, Lot 366, Grave 4)]

Today, the poinsettia is inseparable from Christmas itself, its red bracts and green leaves forming a visual shorthand for the season. That transformation began not in a laboratory or corporate office, but in the hands of a patient farmer working Hollywood soil—testing, failing, starting over, and believing that beauty could be made durable.

Albert Ecke never lived to see his flower conquer the continent. But every December, when poinsettias reappear as if summoned by tradition alone, they quietly testify to his legacy: a man who gave Christmas its color, and Hollywood Forever one of its most enduring immortals.

We invite readers to share their thoughts, memories, and reflections on Albert Ecke, the poinsettia’s journey, and how this Christmas flower has become part of their own holiday traditions in the comments below.

Add comment

Comments